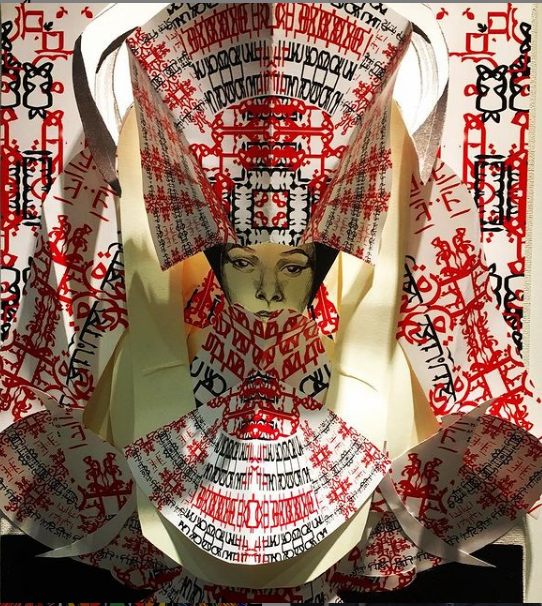

The idea came from a visit to the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) to see and write a BMoreArt review of A Perfect Power, their newest exhibition on African objects. While there, I briefly took off my own mask to wipe my face, and the guards quickly reminded me to put it back on. It got me thinking about the changing meaning of masks through societies and history. The masks in the exhibition, for instance, were all worn by men but were made to call on a higher mother power, a creative force that reigns supreme in the matrifocal cultures in Africa. Were they always worn by men, though? Or did that change with colonization and the subsequent gender roles it assigned onto different societies? When, in other words, were women shamed for being fully present in a public sphere?

The lead cultural consultant for the show, Yoruba scholar Dr. Oyeronke Oyewumi, told me in my interview with her that Yoruba society didn’t use gender in the same way the West does- instead, social roles were designated through seniority.

As for why I’m posting this right now? It’s because of a story that the BMA curator told me about the Ivory Coast, where 40,000 women bared their chests (or wore leaves, or all black) in order to end The Second Ivorian Civil War. Also, if white people can show their whole ass by storming the Capitol, then a little body paint and censored boob action shouldn’t hurt anybody.

By posting this, I’m honoring my fellow body painter and friend (Kitakiya Dennis), a dear spiritual ancestor that frequently used body paint (Michael B. Platt), and my own roots/indigeniety from Mother Africa herself, which I’m still in the process of discovering. The show is no longer open to the public, but the books and writings germane to the profiled societies are available to rent or buy online. I highly recommend Oyewumi’s The Invention of Women, a text that has been celebrated by activist Alok Vaid Menon and others. Ashe and onward.

(The D’mba array, the crown jewel of the show, is from the Baga people of Guinea.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed